The aim of the research project Street Art in Istanbul was to look at the diversity of art in the public space. The widespread use of art – from political purposes to aesthetic reasons – demonstrates the diverse ideas of artists and city dwellers to live with and within their city. Lea Stöver‘s research project is part of the seminar “Global City Istanbul”.

Within the Gezi Park protests the penguin became a powerful symbol visible all over Istanbul. This happened after the Turkish TV broadcasted a documentary about penguins instead of reporting the protests. At that time, dozens of symbols, tags, murals etc. were expressing the ideas and claims of the protests. Learning about this from German media, I began to ask whether, during the protest, street art became a medium of expression. Furthermore, was street art a feasible way to oppose official media dominated by censorship and political arbitrariness? And does this mean that people doing street art realize what David Harvey calls “the right to the city”?

But first of all, what is street art? The philosopher Nicholas A. Riggle highlights three characteristics in his attempt to define street art: the anonymity of the artists, the disconnection of street art from the art world and its power to engage the masses. 1 For Riggle, these characteristics arise from the way street art uses public space in a double sense: First, the street is used in its physical composition and becomes an “artistic resource” 2; second, the fact that street art is public and ephemeral becomes meaningful to the art. Riggle concludes: “An artwork is street art if, and only if, its material use of the street is internal to its meaning.” 3 This approach might help to understand why street art could become a medium within the Gezi Park protests. Among other things, these protests were directed against mega projects of urban transformation in Istanbul, processes transforming the city and changing the rights to live in and with it. According to David Harvey, the right to the city includes not only the right to use the resources of a city individually or conjointly but also the right to change the city and to reinvent it again and again. 4 This leads to the question whether street art in Istanbul appearing during the protests in 2013 struggled for the right to the city by using the street as a medium.

By May 2014, the street art created during the protests in 2013 had been “deleted” (that means covered up with grey and white paint). The results of this “cleaning” were still visible all over Beyoğlu, but especially in the Gezi Park. Physically, the Park was retransformed from the center of protests back to an ordinary park, but this transformation did not stay invisible. The trees in Gezi Park whose planned cutting caused the beginning of the protests, were full of grey and white spots covering up writing or stencils made during the protests.

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

M., a street artist and expert on the scene, drew the following comparison:

“AKP and Recep Tayyip they are so much pressing on the press, the media, on documentaries, anywhere. So they are doing the same thing to street art as well.” 5

He explained how fast graffiti and stencils made by the protesters containing political messages were covered by the police or staff from the municipality. Sometimes, this happened just hours after the graffiti or stencils were painted.

But walking through Beyoğlu, Taksim, Gezi Park, Cihangir and Kadiköy showed me that street art in Istanbul is still vibrant and diverse. Hence, I was not able to confirm or withdraw my initial assumption about street art as a claim for the right to the city. But the different purposes of street art I identified make clear that Nicholas A. Riggle’s characterization needs to be differentiated and that street art in Istanbul may be seen as a reflection of different, opposing ideas of how to live in and with the city. In the light of the events of the year 2013, it is probably most interesting to examine how street art finds itself between commodification and economic needs on the one hand and as a medium of the protest against a government that furthers precisely these ideas and values within a new state capitalism on the other hand. Therefore, street art in Istanbul cannot be subsumed under the mere slogan of art in the public space but must be researched in a more differentiated manner.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Cf. Riggle, Nicholas A.: “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces”, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68 (2010) 3, pp. 243-257, here p. 243. ↩

- 2 Riggle, Nicholas A.: “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces”, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68 (2010) 3, pp. 243-257, here p. 245. ↩

- 3 Riggle, Nicholas A.: “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces”, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68 (2010) 3, pp. 243-257, here p. 246. ↩

- 4 Harvey, David: Rebellische Städte, Berlin: Suhrkamp 2013, p. 28. ↩

- 5 Interview with M. on May 25, 2014. ↩

The side streets of İstiklâl Caddesi are dominated by the art of Luxury Hands, a company founded by six street artists, amongst them Leo Lunatic and Mr. Hure. You find pandas, spray cans, tags and other symbols typically used by these artists all over Beyoğlu. Nur-i Ziya Sokak, a small street off İstiklâl Caddesi, is just one example. When entering this street, you are welcomed by one of Leo Lunatics pandas, a small café follows. The owner of the café explained to me that the artist was his friend. Leo Lunatic and his colleagues from Luxury Hands painted the walls around the café. But this is not all – along the small street, downhill, there are more murals and tags by the same artists.

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

Besides the grey and white spots, this kind of street art is the most visible around İstiklâl Caddesi. This simultaneity of pandas and white spots demonstrates that there is an art which is accepted by the municipality and another which is unwanted or even feared. The art and the activities of Leo Lunatic and his colleagues are accepted. Some of their murals are directly tagged on facebook, twitter and instagram. Even if you cannot find their real names via social media, you can contact them and see them on photos or videos. This means they willingly break their anonymity. Therefore, the category of street art must be broadened again: Street artists in Istanbul can be popular and their art can be accepted by the municipality and population. This art carries no explicit political message in itself but becomes political in contrast to the white spots surrounding it.

Mixer is an art gallery in Tophane which opened in 2012 and pursues the aim of broadening and supporting the contemporary art scene in Istanbul. They provide an exhibition space for young Turkish artists and offer the art works to the public for an affordable price. From May 9 to June 15, 2014, the exhibition “Erör” showed the works of Cins, a street artist from Istanbul:

“As a continuation of the artist’s recent graffiti works, Cins depicts organic forms that recall flesh and meat on found objects, canvas, and paper in his new works. A site-specific graffiti on the exterior wall of Mixer will flow into the exhibition area, creating a unity with the artist’s drawings, collages, and paintings.“ 1

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

Talking to a staff member of the gallery, I learned that Cins had already exhibited his works at their art space before and that he came up with the idea of doing of a whole exhibition about it. The team of Mixer discussed whether the art of a street artist could be exhibited in a gallery, but eventually decided that everyone would profit from this exhibition: Visitors who were not interested in street art before could explore Cins’ art in a gallery; and the artist, whose art becomes visible to a greater number of people can eventually sell his art. The staff member admitted that of course, Cins’ art is a different one in the gallery than it is on the street, since one of the main characteristics of street art – being painted in a public space – gets lost. Nevertheless, his personal style remains the same, just put on a canvas. Cins aimed at protecting his anonymity. He attended the exhibition opening without being introduced to the visitors, thus staying unrecognized. Therefore, he struggled partially against his entrance to what Nicholas A. Riggle calls “the art world”. 2

Maybe there is a space for this kind of street art different from the art world defined as “classical” where an artist’s identity is strongly connected to their works. In that space, street art indeed loses its ephemeral and public character by being exhibited. However, this does not prevent the artist from continuing their work in the street. Eventually, the movement from the street to the gallery draws the attention to the contradictions of street art inside: The transcience of art and the purpose of shaping the public space on the one hand, its commodification and the purpose of being paid for the art work on the other hand.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Flyer by Mixer Gallery, announcing the exhibition “Erör”. ↩

- 2 For Riggle, “Street art is deeply antithetical to the art world” Riggle, Nicholas A.: “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces”, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68 (2010) 3, pp. 243-257, here p. 248. For him, the art world takes place at the museum, where a strong differentiation between the everyday and art is maintained. Without defining his understanding of the term, Riggle implicitly imagines it as a network of institutions, particular actors and knowledge. This network is able to draw the line between art and non-art. ↩

“No street art is for people on the street, you cannot use it for a medium of free advertisement, you have to pay your tax to if you want to make a puma ad, or if you want to make a puma ad with the culture of street art you have to pay some street artists to paint something for you. It’s not just like giving the stencil free and then giving paint and also stencils and go out and ps ps ps run away, it’s just too rude, it’s too rude to the culture. It’s not street art.” 1

On the İstiklal Caddesi and the surrounding streets, I found stencils advertising Puma and Red Bull. Some of them were painted just on the white and grey spots covering up other stencils or graffiti painted during the protests. But this chain of covering is repeated: The stencils of Puma and Red Bull are crossed out expressing discomfort with this appropriation of street art techniques by multinational companies for advertising purposes.

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

M. expressed his rejection of this practice during our interview; emphasizing that street art should not be used this way. Nevertheless, one can find another kind of street art advertisement in Istanbul: There is a huge panda painted by Leo Lunatic next to the Galata Tower. This mural is an advertisement for Converse. Even if the purpose of advertising challenges the category of street art, the “material use of the street is internal to its meaning” 2. But another important characteristic of street art introduced earlier collapses: The artist is not anonymous; the artist promotes himself on social media and even in a video showing him paint a similar mural, an advertisement for Eastpak.

- © Lea Stöver 2014

- © Lea Stöver 2014

Certainly, Leo Lunatic and his Converse Panda as well as the stencils advertising Puma and Red Bull challenge the category of street art. Yet, in both cases different characteristics of street art are used: The effortlessness of painting a lot in a short time in the first instance, popularity and “street credibility” in the second instance. Therefore, the category of street art should be differentiated within itself: Street art in Istanbul is commercial as well.

In May 2013, I could not find any street art left from the protests. Rather, I found numerous white and grey spots indicating that using the materiality of the city had played a role during the protests. The street artist and expert M. concluded this as follows:

“And so many people just started taking attention to taking pictures of the street art, like oh this is really funny, this is really good, this is protest, this is, taking a picture with. So it really opened people’s mind, you can just put out what you are thinking on the street and other people react to it or taking a picture, sharing, commenting. So I think just not only Gezi Park of course but it has a huge effect as well to opening people’s mind to looking more to the walls. Because during that time not newspapers, not TV channels, they are not really broadcasting what’s going on, so people are actually getting the News from the social media, from different friends and stuff. So writing some stuff on the wall was really meaning a lot.” 1

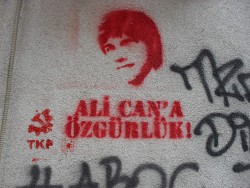

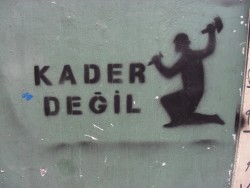

Even if this “stuff” is mostly covered, you still can find stencils or murals expressing opposition to the ruling government and President Erdoğan. Mostly in Kadiköy I discovered stencils objecting to the official statements about the mining accident in Soma in May 2014. 2 Erdoğan compared the disaster to mine accidents in England in the 19th century and declared them to be common in this kind of business, to be fate. 3 During demonstrations in Istanbul and several other Turkish cities, people expressed their anger about these comments.

While taking photos of one of these stencils, a group of five men observed me. They were sitting on a balcony, facing this stencil.

I asked them if they could translate for me. One of them explained to me that it showed a boy who died during the protests. 4 Then he asked me what I thought about Erdoğan. As I was not sure about his opinion, I tried to answer very carefully – I rather wanted to know what he thought. He did keep me guessing, and stated: “He is like Hitler.” My nationality was already clear at that moment, so I guess it had some influence on the comparison he drew. For him, Erdoğan was a dictator since he oppresses every kind of opposition or disagreement to his politics. What was most interesting to me was that, as I was taking a picture of a stencil, people wanted to talk to me, to discuss, to share their opinion. Even if street art remains undiscovered or neglected by many people, this incident shows that “writing some stuff on the wall was really meaning a lot”, as M. concluded earlier.

These examples show that people use the techniques of street art in Istanbul to oppose against official statements and to express their opinion in the public space. Here, street art is political. These findings allow me to conclude that street art became a medium during the protests and was still used as such in May 2014. The high degree of anonymity and rapidness of doing stencils made this technique so prominent.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Interview with M. on May, 25 2014. ↩

- 2 I would like to thank Fulden Eskidelvan who helped me with the translation of the slogans. ↩

- 3 Cf. Scott, Alev: “Erdoğan’s self-defence over Soma’s mining disaster was badly misjudged”, the guardian, May 15, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/may/15/erdogan-turkey-mining-disaster-turkish-prime-minister (last accessed July 2015); Katrin Elger et al: “Soma Tragedy: Erdogan Faces Fall-Out From Mine Disaster”, Spiegel Online International, May 19, 2014, transl. Jane Paulick, http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/soma-mine-disaster-reveals-cracks-in-turkish-leadership-a-970284-2.html (accessed 9 March, 2015). ↩

- 4 As I learned later, the slogan says “Freedom for Ali Can”. Ali Can is a student who was arrested during the protests. ↩