As a research group, we were concerned with Istanbul’s economical, cultural and social transformation into a global city over the past 50 years as well as the various effects of this transformation. During our travel to Istanbul Nora Kühnert and Anne Patscheider conducted field research on squatting in Istanbul. The political controversies regarding common usage of urban space in everyday life as well as the political struggles stemming from immense changes of social life culminating in the Gezi Park protest in 2013 were the most obvious links between the projects that they visited.

By the changing shape of the Istanbul skyline, the rapid growth of production within the city since the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) rose to power in 2002 is easily visible to the city’s inhabitants. Over the past two decades, Istanbul has undergone a neoliberal restructuring process. 1 Progressing globalization and digitalization have not only turned the city into a site absorbing surplus value – an epicenter of the accumulation of capital – they have also formed a new urban space in which traditional national spatial arrangements engage with those of the global digital age. 2

As a research group, we were concerned with Istanbul’s economic, cultural and social transformation into a global city over the past 50 years as well as the various effects of this transformation. During our travel to Istanbul from May 23, until May 31, 2014, we conducted field research on squatting in Istanbul. The political controversies regarding common usage of urban space in everyday life as well as the political struggles stemming from immense changes of social life culminating in the Gezi Park protest in 2013 were the most obvious links between the projects we visited.

In reference to David Harveys’ “Rebel Cities”, we call people’s occupation of Taksim Square “their right to the city” 3. In our field research, we intended to explore the political intentions of The Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, a squat in Istanbul German leftist magazines focused on, calling it a “follow-up movement to Gezi.” 4 We asked ourselves in which way squatting in Istanbul is connected to the 2013 Gezi Park protest movement and how it relates to neoliberal politics and urban transformation. Our first associations were with squatting forms to be found in European countries such as Spain or Greece familiar to us. There, activists occupy houses in order to live in them. Reading David Harvey helped us understand the Gezi Park movement. Therefore, we presumed that his theory might also be of help in grasping squatting in Istanbul. Hence, we strove to comprehend the possibilities and difficulties connected to squatting as a resistance practice: 5 for example, we were concerned with the composition of squatting groups as well as their political aims and demands.

Research

We conducted our main research at Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi. This social center was set up by a network of squatting groups in Istanbul as well as related political agents encouraged by economical processes beyond the squatting scene. We hoped that brief stays at Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, the Caferağa Dayanışması, the Komşu Kafe and Samsa Bay, participant observation and guided interviews would provide insight into the inner configuration of Istanbul’s squatting scene. We interviewed people involved at the time of our research, asked them to draw mind maps of the squatting scene and questioned them about its constellation as well as their opinions on perspectives of resistance in Istanbul. In order to get an overview of the connections and networks of the squatting scene, we extended our fieldwork to interviewing a political activist who was a member of the 1970’s leftist movement. We also added attending lectures by Tuna Kuyucu 6 and Biray Kolluoğlu 7 at Boğaziçi University on neo-liberal politics in Istanbul and its effects on urban transformation and the social life in the city.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Kullouğlu, Biray/Candan, Ayfer Bartu: Emerging Spaces of Neoliberalism: “A gated Town and a Public Housing Project in Istanbul”, in: New Perspectives on Turkey 39 (2008) fall, pp. 5-47, here p. 5. ↩

- 2 Sassen, Saskia: The Global City – The De-Nationalization of Time and Space, http://90.146.8.18/en/archiv_files/20021/E2002_018.pdf (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 3 Harvey, David: Rebel Cities. From The Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, London/New York, NY: verso books 2012. ↩

- 4 Umul, Fatma: “Istanbul-Yeldegirmeni. Wir sind alle Don Quijote”, in: AK- Analyse und Kritik. Zeitung für linke Debatte und Praxis 590 (2014), http://www.akweb.de/ak_s/ak590/21.htm (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 5 In the field of European Ethnology, the term “practice” is used to describe a certain way of investigating cultural phenomena. Classifying squatting as a resistant practice, we took a look at the past of resistance in Istanbul and how it is presently done in daily situations in the squats. Our definition of resistant practice refers to Henri Lefebvres and denotes an active or resistant intervention in the social production of space challenging the dominant production of space and temporarily creating a space of its own in opposition to it. ↩

- 6 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 7 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Biray Kolluoğlu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Global City Istanbul: Urban Transformation and ‘Gated Communities’, May 26, 2014. ↩

After the Gezi Park protests were put to an end in the summer of 2013, people started to get together in local neighborhood parks and founded so-called neighborhood “forums.” Some protesters wished to maintain the often-mentioned “Gezi spirit”: They wanted to keep discussing political demands or ways of organizing amongst themselves. At this point, the slogan “Everywhere Taksim – Everywhere Resistance” was established beyond the borders of Turkey. As the year passed and the weather grew too cold for these weekly assemblies, the activists of the “Yeldeğirmeni solidarity (Dayanışması)” forum in Kadıköy started discussing the option of occupying an empty building.

Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi

Stemming from these forums, “Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi” (Don Quijote Social Centre) came into existence. The property concerned had been abandoned for many years. It was considered suitable for an occupation as a result of its ownership rights being disputed. In the beginning, the newly formed community came together to renovate the shell of the building. Everybody involved worked voluntarily, often in addition to a day job or studying. In the meantime, two weekly assemblies were formed to discuss issues concerning the social center or political activities people were interested in. Apart from the assemblies, people got together to socialize, eat together and play games but also to do workshops or plan political activities. The property is spacious enough for art exhibitions and graffiti. On the upper floor, participants installed a give-away or sharing shop and experimented with indoor gardening. The main reason for occupying the building cited by the activists was to reinforce neighborhood solidarity. Another aim was to reorganize and reshape social space in a way “commons” are created.

- Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

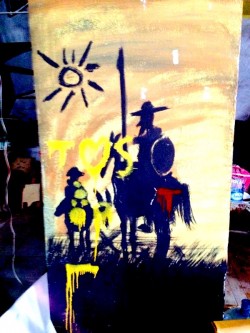

- Graffiti inside of the Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Graffiti inside of the Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

Komşu Kafe

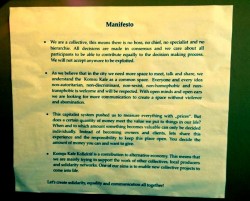

The Komşu Kafe Collective is an autonomous, self-organized café in Kadıköy existing since summer 2013 and, like the Don Kişot social center, was opened in the “Gezi spirit.” Naming the café “Komşu” (English “neighbor”) emphasizes that everyone is invited to participate. In the manifesto, Komşu Kafe is described as a common space due to a perceived citywide lack of such space. In the café, everyone shall feel equal and autonomous at the same time. Every person is free to go behind the counter to prepare hot beverages for themselves or for others and people are free to pay whatever they can afford. The Komşu-Collectivistas see their concept as a contribution to an alternative economy undermining the capitalist system.

- The Komşu Kafe, Kadıköy, Istanbul ©https://goo.gl/vQCL9z

- The Komşu Kafe, Kadıköy, Istanbul ©https://goo.gl/jiF4gU

- The self-given Komşu-Kafe Manifeste, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 27.05.2015, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

Samsa Squat

Several former Don Kişot activists no longer supporting all decisions regarding the social center in the Duatepe Street decided to squat in another building in Kadıköy near the Sali market. The start of their disagreement was a padlock installed at the social center’s door. In the eyes of some squat activists, this was a mechanism of exclusion creating hierarchies. Furthermore, the activists meant to create a place that was more than a social center: A squat as known in various European cities such as Barcelona, Milan, Athens, Amsterdam or Berlin, a squat to not only have political meetings in but also to live collectively. The squat was called Samsa, after Gregor Samsa, the protagonist of Franz Kafkas “The Metamorphosis.” The name was chosen as a reference to the Don Kişot Social Centre named after Miguel de Cervantes’ novel. One of the founding members of the Samsa Squat told us he wanted to live his life as far as possible outside of “the system.” To him, this meant resistance in everyday life: not being part of consumerism at all. He and many activists of the Kadıköy squatting scene want people and neighbors to organize every aspect of their life by themselves in form of a direct democracy. Therefore, concepts like “solidarity”, “neighborhood” and “autonomy” as well as “collectiveness” are important, constituent parts of their political approach, which can be described as “creating commons”.

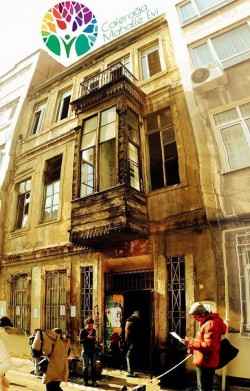

Caferağa Dayanışması Mahalle Evi

The Caferağa Dayanışması (Caferaga Solidarity) is another squatting community center in Kadiköy. When the after-Gezi activists of the Yeldeğirmeni Solidarity Forum decided to occupy the building, it was abandoned and in need of an enormous amount of renovation. From the squat’s facebook page and blog posts, we gathered that it had been evicted by the Turkish Riot Police on the 9th of December 2014. A report of the events can be found via the following link:

- Caferağa Dayanışması, free library, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Caferağa Dayanışması, Art installation for the victims of Soma, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Caferağa Dayanışması Mahalle Evi, Kadıköy, Istanbul, ©http://goo.gl/pClflK

In Istanbul, we did not discover just one squat but a whole squatting scene. The squats in Kadıköy were rarely used as places to live in. Participants told us that they do try to learn from squats in Europe like in Spain or Greece, but that Istanbul’s squats mainly function as neighborhood forums. They are autonomous social centers of their respective neighborhoods. Through the squats, volunteers get in contact with their neighbors to brainstorm and discuss problems emerging for example from urbanization policies in Istanbul. In addition, the social centers are places to spend time together. They are meeting points for activists, (Erasmus) students, artists or employees exchanging political ideas and concepts of practices. Due to one of the participants, occupying houses in Istanbul is not about taking over new places to live but rather about creating a space for your own way of living and thinking. The activists want to establish squatting in Istanbul like in Spain and Greece and say that they want to learn from the experiences made in these countries.

(Im)Possibilities of neighborhood forums and resistance practices in Istanbul

All activists we interviewed mostly referred to Harvey, Hardt as well as Negri and described the squats as an attempt of “commons” materializing the goal of reclaiming urban spaces. Like occupying Taksim, squatting can be read as a call for the right to participate in Istanbul’s spatial and material development as well as an attempt to resist neo-liberal politics, gentrification and expropriation connected to Istanbul steadily developing into a global city, which is kind of a “brutal place” 1 to live in. In a recent publication called “Cool Istanbul – Urban Enclosures and Resistances” based on a conference in November 2013 related to a DFG-funded project, Aras Özgü provided an outlook on the future of upcoming resistance in Istanbul. He emphasized

“that Gezi Park protests brought an important novelty to Turkish radical politics […], the protesters reclaimed the urban commons that had been taken from them.” 2 Squats in Istanbul are an actual continuation of radical politics of similar importance and intentions. By creating a place that connects subversive artistic politics with radical practices, they are facing a great number of challenges: When asked about the squatting scene’s perspectives, participants active in Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi emphasized the fact that political commitment while studying or/and having a job required a lot of energy. Everybody is working at their neighborhood forums voluntarily; most of the participants are students, artists or middle class workers. Most of the time, there is not even enough energy available to discuss the different political aims while also maintaining an everyday life as a precarious worker. Establishing contact with recent migrants or minorities living in highly conflict laden neighborhoods and the articulation of their interests in the city could not be achieved in full. Thus, in order to generate solidarity, the activists focused on the direct needs of the neighborhood instead. Again, the goals of those marginalized by neo-liberal policies and the global city such as transnational migrants and minority groups could not be included in an established form of political commitment.

The various legal changes to the status quo alter the way the global city Istanbul develops in such a drastic and rapid way that even the squatting of buildings cannot impede. If the Yeldeğirmeni or Kadıköy districts become more profitable for private or public-private investors in the future, the political desire to clear the area of subversive, anti-capitalist projects like cafés or neighborhood forums will develop. It is questionable whether the new forms of solidarity present in the Kadıköy neighborhoods will spread to other districts and generate a wider movement of people searching for and building different forms of non-profitable relationships within capitalist society due to the rather small numbers of people committed to squatting.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Meister, Franziska: “Interview mit Saskia Sassen: ‘Die Global City ist ein brutaler Ort‘”, in: Die Wochenzeitung 25 (2012), https://www.woz.ch/-2ea1 (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 2 Özgün, Aras: “The Value of Art and the Political Economy of Cool”, in: Özkan, Derya: Cool Istanbul. Urban Enclosures and Resistances, Bielefeld: Transcript 2015, pp. 35-61, here p. 56. ↩