As a research group, we were concerned with Istanbul’s economical, cultural and social transformation into a global city over the past 50 years as well as the various effects of this transformation. During our travel to Istanbul Nora Kühnert and Anne Patscheider conducted field research on squatting in Istanbul. The political controversies regarding common usage of urban space in everyday life as well as the political struggles stemming from immense changes of social life culminating in the Gezi Park protest in 2013 were the most obvious links between the projects that they visited.

By the changing shape of the Istanbul skyline, the rapid growth of production within the city since the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) rose to power in 2002 is easily visible to the city’s inhabitants. Over the past two decades, Istanbul has undergone a neoliberal restructuring process. 1 Progressing globalization and digitalization have not only turned the city into a site absorbing surplus value – an epicenter of the accumulation of capital – they have also formed a new urban space in which traditional national spatial arrangements engage with those of the global digital age. 2

As a research group, we were concerned with Istanbul’s economic, cultural and social transformation into a global city over the past 50 years as well as the various effects of this transformation. During our travel to Istanbul from May 23, until May 31, 2014, we conducted field research on squatting in Istanbul. The political controversies regarding common usage of urban space in everyday life as well as the political struggles stemming from immense changes of social life culminating in the Gezi Park protest in 2013 were the most obvious links between the projects we visited.

In reference to David Harveys’ “Rebel Cities”, we call people’s occupation of Taksim Square “their right to the city” 3. In our field research, we intended to explore the political intentions of The Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, a squat in Istanbul German leftist magazines focused on, calling it a “follow-up movement to Gezi.” 4 We asked ourselves in which way squatting in Istanbul is connected to the 2013 Gezi Park protest movement and how it relates to neoliberal politics and urban transformation. Our first associations were with squatting forms to be found in European countries such as Spain or Greece familiar to us. There, activists occupy houses in order to live in them. Reading David Harvey helped us understand the Gezi Park movement. Therefore, we presumed that his theory might also be of help in grasping squatting in Istanbul. Hence, we strove to comprehend the possibilities and difficulties connected to squatting as a resistance practice: 5 for example, we were concerned with the composition of squatting groups as well as their political aims and demands.

Research

We conducted our main research at Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi. This social center was set up by a network of squatting groups in Istanbul as well as related political agents encouraged by economical processes beyond the squatting scene. We hoped that brief stays at Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, the Caferağa Dayanışması, the Komşu Kafe and Samsa Bay, participant observation and guided interviews would provide insight into the inner configuration of Istanbul’s squatting scene. We interviewed people involved at the time of our research, asked them to draw mind maps of the squatting scene and questioned them about its constellation as well as their opinions on perspectives of resistance in Istanbul. In order to get an overview of the connections and networks of the squatting scene, we extended our fieldwork to interviewing a political activist who was a member of the 1970’s leftist movement. We also added attending lectures by Tuna Kuyucu 6 and Biray Kolluoğlu 7 at Boğaziçi University on neo-liberal politics in Istanbul and its effects on urban transformation and the social life in the city.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Kullouğlu, Biray/Candan, Ayfer Bartu: Emerging Spaces of Neoliberalism: “A gated Town and a Public Housing Project in Istanbul”, in: New Perspectives on Turkey 39 (2008) fall, pp. 5-47, here p. 5. ↩

- 2 Sassen, Saskia: The Global City – The De-Nationalization of Time and Space, http://90.146.8.18/en/archiv_files/20021/E2002_018.pdf (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 3 Harvey, David: Rebel Cities. From The Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, London/New York, NY: verso books 2012. ↩

- 4 Umul, Fatma: “Istanbul-Yeldegirmeni. Wir sind alle Don Quijote”, in: AK- Analyse und Kritik. Zeitung für linke Debatte und Praxis 590 (2014), http://www.akweb.de/ak_s/ak590/21.htm (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 5 In the field of European Ethnology, the term “practice” is used to describe a certain way of investigating cultural phenomena. Classifying squatting as a resistant practice, we took a look at the past of resistance in Istanbul and how it is presently done in daily situations in the squats. Our definition of resistant practice refers to Henri Lefebvres and denotes an active or resistant intervention in the social production of space challenging the dominant production of space and temporarily creating a space of its own in opposition to it. ↩

- 6 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 7 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Biray Kolluoğlu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Global City Istanbul: Urban Transformation and ‘Gated Communities’, May 26, 2014. ↩

As a result of successful education and health politics in Turkey during the 1930s, the infant mortality rate declined and population increased. After the Second World War, the distribution of work opportunities led to a massive migration of Anatolian peasants to Istanbul. Due to a lack of housing, copious so-called gecekondus were “built over night,” resulting in sprawling urban growth. 1 Based on a specific customary law remnant of Ottoman times, those who were able to build a shack overnight could stay and live on that exact spot of land. In Ottoman times, all land belonged to the Sultan; individuals could only attain usage rights if they used it in ways benefiting the Sultan and paid taxes. 2

From the beginning of this migration wave until the 1970s, gecekondus were not only built to satisfy existential needs such as the necessity of a place to live, but also constituted political tools displaying inequalities between migrants and long-established residents. Gecekondu neighborhoods operated via informal markets and through networks of kinship as well as local relationships devoid of governmental regulations. They gained the solidarity of the middle class, the leftist movement and syndicates 3. From the 1980s onward, the value of gecekondus increased due to the increasing scarcity of space caused by growing urbanization. As investors and state administration became aware of this process, they offered the land occupiers the opportunity to expand their houses, to rent or to sell them. From that moment on, the gecekondu neighborhoods were no longer merely a means to satisfy the migrants’ existential needs, but became an opportunity to join the formal market and accumulate capital 4. A political protest in form of land appropriation by gecekondu owners thus became obsolete for those able to ascend into the middle class. 5 The new elites of Istanbul often call this form of material production a unique urban disaster. Orhan Esen claims it to be a resource of collective experience for Istanbul’s citizens, calling it self-service urbanization. 6

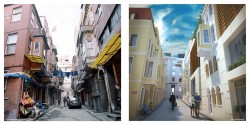

Since the 1990s, various districts are more and more affected by gentrification: Because of immense increases in rent, the “established” inhabitants are often forced to move out of their districts. 7 When visiting Istanbul, we took a guided tour through the city lead by Ayşe Çavdar. She showed us to the borders of the district Tarlabaşı and explained the district’s transformation during the past two decades. Among Istanbul’s districts, Tarlabaşı in particular is inhabited by transnational migrants from Africa and Asia as well as marginalized groups like Kurds, Roma or transsexuals. While it was spared from drastic changes during the 1990s, it has become a so called “regeneration area” since 2006. The Çalık-Holding was assigned to conduct a large-scale construction project designed to replace the old, often decayed buildings with modern ones. As the present inhabitants are unlikely to be able to afford the massively increased rents, they will presumably have to move away. The buildings not being demolished may also become items of private speculation resulting in drastically rising rents and the eviction and displacement of minorities as well. 8

Fußnoten:

- 1 Cf. Esen, Orhan: “Learning from Istanbul. The city of Istanbul: Material production and production of the discourse”, in: Esen, Orhan/Lanz, Stephan (eds.): Self Service City: Istanbul, Berlin: b_books 2006, p. 35. ↩

- 2 Esen, Orhan: “Learning from Istanbul. The city of Istanbul: Material production and production of the discourse”, in: Esen, Orhan/Lanz, Stephan (eds.): Self Service City: Istanbul, Berlin: b_books 2006, p. 37. ↩

- 3 Cf. Erder, Sema: “Where do you hail from? Localism and networks in Istanbul”, in: Keyder, Caglar (ed.): Istanbul. Between the Global and the Local, Boston, MA: Rowmann& Littlefield 1999, pp. 161-173, here p. 163. ↩

- 4 Cf. Erder, Sema: “Where do you hail from? Localism and networks in Istanbul”, in: Keyder, Caglar (ed.): Istanbul. Between the Global and the Local, Boston, MA: Rowmann& Littlefield 1999, pp. 161-173, here p. 164. ↩

- 5 Esen, Orhan: “Learning from Istanbul. The city of Istanbul: Material production and production of the discourse”, in: Esen, Orhan/Lanz, Stephan (eds.): Self Service City: Istanbul, Berlin: b_books 2006, p. 41. ↩

- 6 Esen, Orhan: “Learning from Istanbul. The city of Istanbul: Material production and production of the discourse”, in: Esen, Orhan/Lanz, Stephan (eds.): Self Service City: Istanbul, Berlin: b_books 2006, p. 33. ↩

- 7 Gottschlich, Jürgen: “Gentrifizierung in Istanbul. Raus mit allen Underdogs“, in: taz, June 11, 2012 http://www.taz.de/!95032/ (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 8 Gottschlich, Jürgen: “Gentrifizierung in Istanbul. Raus mit allen Underdogs“, in: taz, June 11, 2012 http://www.taz.de/!95032/ (last accessed July 2015). ↩

When confronted with the huge urban transformation of Istanbul since the 1960s, we asked ourselves which laws and projects adopted by Erdoğan in the more recent past had led to the present forms of urbanization and its results, e.g. the regeneration areas. AKP politics were based on earlier neo-liberalization processes led by Turgut Özal, founder of the AKP’s predecessor party ANAP and Turkey’s prime minister after the end of the military dictatorship. During the Özal era, neo-liberal “foundation stones” were established, among them the privatization of publicly owned enterprises, the decrease of the so-called welfare state, the deregulation of markets, the opening of the country for transnational flows of goods and capital as well as, of course, an ongoing cooperation with institutions like the World Bank 1. This neo-liberal turnabout implemented by Özal’s government had already been planned during the military dictatorship. 2

With Erdoğan being a former mayor of Istanbul, a prime minister taking enormous interest in Turkey’s biggest city and only metropolis was elected. Erdoğan established a new form of housing and construction policies mainly by deploying public-private partnerships, but also by maintaining and furthering privatization. His state policy was and still is ensuring economic growth through modernization and liberalization, though this end is not necessarily achieved through the creation of free and accessible markets. Turkey’s government implemented a specific form of “state capitalism” consisting in the establishment of national companies which are non-public yet controlled by the state. Through their openness for investments by global firms and investors, these companies are intertwined with transnational cash flows. A key player in this game surely is TOKI. 3

TOKI

TOKI is a housing development association formed by the government in the 1980s in order to provide low-income housing for municipalities. In 2002, TOKI was formally privatized and assigned an independent budget. Although officially independent, TOKI still operates directly under the prime minister’s control. To facilitate the government’s attempt to renew, redesign, and redevelop cities in a profitable manner, several laws were passed that drastically changed the way urbanization and the city development proceeds.

TOKI Law

With this law, TOKI was authorized to obtain any plot of government land from the treasury to then privatize it. They can either sell it on the market or form a public-private partnership in order to transform these areas, e.g. as renewal areas. In other words: TOKI has almost absolute zoning and planning authority over every area in Turkey. This includes expropriation of entire districts, no matter if those areas have been inhabited by certain communities for decades. 4

Disaster Law

The Disaster Law was passed in 2012. It allows entire districts to be declared insecure due to earthquake concerns, thus giving tremendous power to the Ministry of Environment and Urban Redevelopment as they can “claim” parts of cities and “redevelop” them. 5

Municipality Law

The Municipality Law is another law that allows ministries or local governments to claim entire areas as common property. This law establishes the interests of the municipality as sufficient justification to claim and clear out areas. In consequence, people living in cities, districts and areas concerned are in danger of being evicted. Shops, houses and infrastructure can be razed to the ground and rebuilt, e.g. by one of Turkey’s many real estate investment trusts.

Nepotism in Istanbul

In some of Istanbul’s areas such as Sulukule or Tarlabaşı , this aspect of political practices of urban renewal can be observed in drastic dimensions. 6 Tarlabaşı constitutes an exemplary case of nepotisms, in this case in the construction sector. The project of redesigning of Tarlabaşı was assigned directly to the president’s son in law in his function of the CEO of the Çalık-Holding. As Ayşe Çavdar puts it, this is a regularly practiced kind of corrupt business venture. 7

Criminal Code

The so-called “criminal code” was passed in 2005. It made informal housing in Turkey illegal for the first time in history. Under this code, people living without a lease can be brought to trial. 8

Megaprojects

“Megaprojects” or “crazy projects”, as they are often called by Erdoğan’s critics and the opposition, are a huge part of the enormous changes the government and its planners are subjecting the city to. They include the construction of a canal in the west of the city, a gigantic third airport in the northwest of the city and a third bridge over the Bosporus. All these projects are being undertaken without involving the population into the decision making process although experts and local initiatives warn against colossal environmental damages. Erdoğans “gigantomania” is often criticized. The movie “Ekümenopolis” (2012) documents numerous of these projects and shows the rage these “crazy projects” evoke.

Megaprojects

- Istanbul Canal Project © https://reclaimistanbul.files.wordpress.com

- 3rd Bridge Project © http://media.roarmag.org

Ekümenopolis

Fußnoten:

- 1 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 2 Toussaint, Eric: “The World Bank’s Support of the Dictatorship in Turkey. Global Research”, in: Global Research, October 12, 2014, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-world-banks-support-of-the-dictatorship-in-turkey-1980-1983/5407446 (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 3 Cf. Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 4 Cf. Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 5 Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

- 6 Seibert, “Thomas: Vertreibung für das Paradies“, in: Potsdamer Neuste Nachrichten, March 27, 2009, http://www.pnn.de/dritte-seite/166138/ (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 7 Guided Walk and Lecture by Ayşe Çavdar: Toki, a Building Society, May 24, 2015. ↩

- 8 Cf. Lecture by Assoc. Prof. Tuna Kuyucu at Boğaziçi, University Istanbul, Department for Sociology: Commodification and Country Ownership in Istanbul, May 26, 2014. ↩

After the Gezi Park protests were put to an end in the summer of 2013, people started to get together in local neighborhood parks and founded so-called neighborhood “forums.” Some protesters wished to maintain the often-mentioned “Gezi spirit”: They wanted to keep discussing political demands or ways of organizing amongst themselves. At this point, the slogan “Everywhere Taksim – Everywhere Resistance” was established beyond the borders of Turkey. As the year passed and the weather grew too cold for these weekly assemblies, the activists of the “Yeldeğirmeni solidarity (Dayanışması)” forum in Kadıköy started discussing the option of occupying an empty building.

Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi

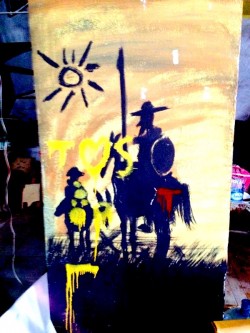

Stemming from these forums, “Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi” (Don Quijote Social Centre) came into existence. The property concerned had been abandoned for many years. It was considered suitable for an occupation as a result of its ownership rights being disputed. In the beginning, the newly formed community came together to renovate the shell of the building. Everybody involved worked voluntarily, often in addition to a day job or studying. In the meantime, two weekly assemblies were formed to discuss issues concerning the social center or political activities people were interested in. Apart from the assemblies, people got together to socialize, eat together and play games but also to do workshops or plan political activities. The property is spacious enough for art exhibitions and graffiti. On the upper floor, participants installed a give-away or sharing shop and experimented with indoor gardening. The main reason for occupying the building cited by the activists was to reinforce neighborhood solidarity. Another aim was to reorganize and reshape social space in a way “commons” are created.

- Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Graffiti inside of the Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Graffiti inside of the Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi, Duatepe st. 10, Kadıköy , Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

Komşu Kafe

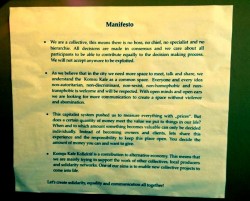

The Komşu Kafe Collective is an autonomous, self-organized café in Kadıköy existing since summer 2013 and, like the Don Kişot social center, was opened in the “Gezi spirit.” Naming the café “Komşu” (English “neighbor”) emphasizes that everyone is invited to participate. In the manifesto, Komşu Kafe is described as a common space due to a perceived citywide lack of such space. In the café, everyone shall feel equal and autonomous at the same time. Every person is free to go behind the counter to prepare hot beverages for themselves or for others and people are free to pay whatever they can afford. The Komşu-Collectivistas see their concept as a contribution to an alternative economy undermining the capitalist system.

- The Komşu Kafe, Kadıköy, Istanbul ©https://goo.gl/vQCL9z

- The Komşu Kafe, Kadıköy, Istanbul ©https://goo.gl/jiF4gU

- The self-given Komşu-Kafe Manifeste, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 27.05.2015, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

Samsa Squat

Several former Don Kişot activists no longer supporting all decisions regarding the social center in the Duatepe Street decided to squat in another building in Kadıköy near the Sali market. The start of their disagreement was a padlock installed at the social center’s door. In the eyes of some squat activists, this was a mechanism of exclusion creating hierarchies. Furthermore, the activists meant to create a place that was more than a social center: A squat as known in various European cities such as Barcelona, Milan, Athens, Amsterdam or Berlin, a squat to not only have political meetings in but also to live collectively. The squat was called Samsa, after Gregor Samsa, the protagonist of Franz Kafkas “The Metamorphosis.” The name was chosen as a reference to the Don Kişot Social Centre named after Miguel de Cervantes’ novel. One of the founding members of the Samsa Squat told us he wanted to live his life as far as possible outside of “the system.” To him, this meant resistance in everyday life: not being part of consumerism at all. He and many activists of the Kadıköy squatting scene want people and neighbors to organize every aspect of their life by themselves in form of a direct democracy. Therefore, concepts like “solidarity”, “neighborhood” and “autonomy” as well as “collectiveness” are important, constituent parts of their political approach, which can be described as “creating commons”.

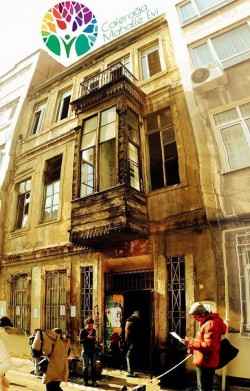

Caferağa Dayanışması Mahalle Evi

The Caferağa Dayanışması (Caferaga Solidarity) is another squatting community center in Kadiköy. When the after-Gezi activists of the Yeldeğirmeni Solidarity Forum decided to occupy the building, it was abandoned and in need of an enormous amount of renovation. From the squat’s facebook page and blog posts, we gathered that it had been evicted by the Turkish Riot Police on the 9th of December 2014. A report of the events can be found via the following link:

- Caferağa Dayanışması, free library, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Caferağa Dayanışması, Art installation for the victims of Soma, Kadıköy, Istanbul, 24.05.2014, © Kühnert, Nora, Patscheider, Anne

- Caferağa Dayanışması Mahalle Evi, Kadıköy, Istanbul, ©http://goo.gl/pClflK

In Istanbul, we did not discover just one squat but a whole squatting scene. The squats in Kadıköy were rarely used as places to live in. Participants told us that they do try to learn from squats in Europe like in Spain or Greece, but that Istanbul’s squats mainly function as neighborhood forums. They are autonomous social centers of their respective neighborhoods. Through the squats, volunteers get in contact with their neighbors to brainstorm and discuss problems emerging for example from urbanization policies in Istanbul. In addition, the social centers are places to spend time together. They are meeting points for activists, (Erasmus) students, artists or employees exchanging political ideas and concepts of practices. Due to one of the participants, occupying houses in Istanbul is not about taking over new places to live but rather about creating a space for your own way of living and thinking. The activists want to establish squatting in Istanbul like in Spain and Greece and say that they want to learn from the experiences made in these countries.

(Im)Possibilities of neighborhood forums and resistance practices in Istanbul

All activists we interviewed mostly referred to Harvey, Hardt as well as Negri and described the squats as an attempt of “commons” materializing the goal of reclaiming urban spaces. Like occupying Taksim, squatting can be read as a call for the right to participate in Istanbul’s spatial and material development as well as an attempt to resist neo-liberal politics, gentrification and expropriation connected to Istanbul steadily developing into a global city, which is kind of a “brutal place” 1 to live in. In a recent publication called “Cool Istanbul – Urban Enclosures and Resistances” based on a conference in November 2013 related to a DFG-funded project, Aras Özgü provided an outlook on the future of upcoming resistance in Istanbul. He emphasized

“that Gezi Park protests brought an important novelty to Turkish radical politics […], the protesters reclaimed the urban commons that had been taken from them.” 2 Squats in Istanbul are an actual continuation of radical politics of similar importance and intentions. By creating a place that connects subversive artistic politics with radical practices, they are facing a great number of challenges: When asked about the squatting scene’s perspectives, participants active in Don Kişot Sosyal Merkezi emphasized the fact that political commitment while studying or/and having a job required a lot of energy. Everybody is working at their neighborhood forums voluntarily; most of the participants are students, artists or middle class workers. Most of the time, there is not even enough energy available to discuss the different political aims while also maintaining an everyday life as a precarious worker. Establishing contact with recent migrants or minorities living in highly conflict laden neighborhoods and the articulation of their interests in the city could not be achieved in full. Thus, in order to generate solidarity, the activists focused on the direct needs of the neighborhood instead. Again, the goals of those marginalized by neo-liberal policies and the global city such as transnational migrants and minority groups could not be included in an established form of political commitment.

The various legal changes to the status quo alter the way the global city Istanbul develops in such a drastic and rapid way that even the squatting of buildings cannot impede. If the Yeldeğirmeni or Kadıköy districts become more profitable for private or public-private investors in the future, the political desire to clear the area of subversive, anti-capitalist projects like cafés or neighborhood forums will develop. It is questionable whether the new forms of solidarity present in the Kadıköy neighborhoods will spread to other districts and generate a wider movement of people searching for and building different forms of non-profitable relationships within capitalist society due to the rather small numbers of people committed to squatting.

Fußnoten:

- 1 Meister, Franziska: “Interview mit Saskia Sassen: ‘Die Global City ist ein brutaler Ort‘”, in: Die Wochenzeitung 25 (2012), https://www.woz.ch/-2ea1 (last accessed July 2015). ↩

- 2 Özgün, Aras: “The Value of Art and the Political Economy of Cool”, in: Özkan, Derya: Cool Istanbul. Urban Enclosures and Resistances, Bielefeld: Transcript 2015, pp. 35-61, here p. 56. ↩